Governor Macquarie proclaimed 29 January 1818 a public holiday in the newly named continent of 'Australia' to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of the landing of the first fleet.

In China, the year of the Yellow Earth-Tiger began on 5 February.

Three weeks later, the Laurel arrived at Port Jackson, Sydney, with a cargo of teas and manufactured goods from India and China. She had left Bengal in August 1817, stayed in the busy port of Guangzhou (‘Canton’) for most of October and November and then called at Malacca and Port Dalrymple (Tasmania) on the way.

Onboard was a young Chinese man in his twenties, a native of Canton, who would later become known as John Shying. But on his arrival, he was known as something like ‘Mark O’Pong’. One of the mysteries is working out what his original name may have been,

The ship’s third officer was George Blaxland, a relative of the more prominent merchant and land-owner John Blaxland. George befriended the man who then became a houseguest at Blaxland’s Newington Estate in Paramatta. He stayed there for about three years and worked as a carpenter.

|

Mak’s host. John Blaxland painting by Richard Read

|

The Blaxland family may well have known ‘Mak’ before the voyage began, as they were merchants at a time of vibrant trade between Australia, India, China, Indonesia and Malacca.

In 1820 he obtained 30 acres of land under the name ‘Mark O'Pong' and was ‘anxious to become an agriculturalist’. He then obtained work with the Macarthur family at Elizabeth Farm also in Paramatta. The Farm’s day-book records him as 'Matchiping' - definitely a mangled pronunciation also.

|

Elizabeth Farm today. The building was renovated in the 1820s.

Plenty of work for Mak. Via Wikipedia |

Mak acquired other land and became Australia’s first Chinese hotel licensee as his prosperity increased.

In 1823, using the name John Shying, he married Sarah Thompson and by 1830 she had borne him three sons. He signed his marriage certificate with an ‘x’, usually indicating that the person signing was illiterate, even though he could have signed in Chinese had he been permitted. He would later claim that he changed his name at the time of marriage from Mark O’Pong ‘as is my country way’.

The origin of the name John Shying is not hard to imagine, even though it sounds nothing like Mark O’Pong. He would have been called ‘John’ by many people who may have found an attempt to pronounce his Chinese name impossible. ‘Shying’, seems to parallel a Chinese given name he used in 1842 for his second marriage when he is recorded in English as ‘John Shying’ but signed his name in Chinese as ‘Mak Sai Ying’ 麥世英. Although it comes first ‘Mak’ was his surname or family name and Sai-Ying although it came last was his given name. The pronunciation is Cantonese which he is presumed to have spoken because that’s where he was born.

|

Mak Sai Ying's signature

from his 1842 wedding. |

However, I have jumped ahead of the chronology…

For some reason in October 1831 with a young wife and four young boys aged 8, 5, 3 and 18 months, he decided to return to China. His reasons are not known. Presumably, he had some kind of obligation – the death of his father, perhaps another family or an irresistible business opportunity…

The point is, his decision was not a whim. He considered what he was doing and made provision for the care of his family through a power of attorney with trustees to manage his affairs. On this occasion, he signed with characters that would sound ‘Mak Sai Pang’ – 麥世鹏. This may well be nearer to his original name and not too far from ‘Mark O’Pong’. Mak as his family name seems a consistent use, as is his middle name Sai (which he might have held in common with any brothers), while the last name is his personal name. There are occasions where he apparently used the name John Pong Shying (which would cover all bases) and, depending on the hearers, there are various spellings for Shying.

|

Mak Sai Pang signature from the 1831 power of attorney.

The final character seems elongated. |

Almost immediately, Sarah Shying in the absence of her husband requested that the deeds to her husband’s land be made over to her indicating that her husband was a native of China and not naturalized. Sounds like she wasn't expecting/wanting him back anytime soon!

The Attorney General responded quickly and with as much sympathy as was legally possible. Naturally, he couldn’t grant the title to a married woman and unfortunately, as her husband was not naturalised he couldn’t own land either. A solution would be for it to be held by trustees for her use and the trustees could dispose of the property to her children – they were all males so it could be passed to them when they were old enough.

Unfortunately, Sarah died in March 1836. John Shying returned to New South Wales, possibly aboard the Orwell which arrived 12 July the same year. If this was his ship, he would have disembarked expecting to find his wife alive. We know that Captain Living ‘brought him down from China to join his family’ and he also noted that ‘he is a very civil, industrious, sober man’ who shows a ‘consistent character among the Europeans who know him in Canton’. No shipping records list him by any of his known names, although occasionally carriage of ‘a Chinaman’ is noted. He may also have been regarded as crew – meaning he could get a lift back and perhaps do some work.

Captain Living’s remarks and Mak's apparent prior friendship with the Blaxlands paints a picture of a man involved with international trading in some way and in regular engagement with Europeans.

|

| Mak Sai Pang’s busy international workplace? Canton view by Louis Lebreton c. 1850 via Pinterest |

After his return, John Shying wrote to Governor Sir Richard Bourke, indicating he'd been in China for the past five years, to have another shot at getting formal title to his land. He mentions that he'd left his affairs in the care of two trustees but had forgotten to write 'a memorandum' before his departure. He indicates he's brought money back with him (presumably unusual) and refers to being deceived by a Mr O'Brien. The letter was presumably written by a scribe but the signature in English is ‘John Shying’ and may be in a different hand.

His request was knocked back by the Governor on the basis of ‘regulations of October 1826 and 1827’.

As mentioned above we know that he married again in 1842. His new wife was Bridget Gillorley though unfortunately she died within four months.

In October 1844 John Shying evidently made a will. The will itself has not been found but it is mentioned in a later deed of 1854 to give effect to the intentions of the will before his actual death – as John Shying the elder seems to be a signatory of the deed. Again he seems to be looking after the financial welfare of his family.

Soon after that, he disappears.

There is no record of his death in or departure from the Colony.

|

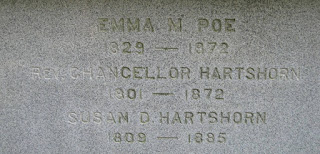

John Sheen’s gravestone.

Picture and grave-clean by Chris Pigott |

However, a fellow named John Sheen appears in 1846 and marries Margaret McGovern in Sydney. Sheen is a few years older than Shying and while he is described as a very old resident of the Colony, there is no other record of him. For his marriage Sheen claims he was born in ‘Chinese India’ - wherever that might be. When Sheen dies in 1880 his undertakers are two of John Shying’s sons.

Members of both the Shying and Sheen families have hoped that evidence will confirm that the two men are the same. It would solve two mysteries; where did Shying go and where did Sheen come from. Documentation has no far not helped and other historians have left it as a family riddle.

This looks like a case for genetic genealogy!

As it turns out, some family historians in 2001 did try a DNA test. The test was conducted by the then-new Department of Forensic Medicine in Sydney. Three samples were collected and two tested, one from the male line in each family. The results clearly indicate that the two men sampled did not have the same male-line ancestors.

This evidence, however, opens up more questions than it answers.

The Shying family have stories of a brother so this provides some hope. Further DNA testing may enable the families to establish a point of origin for their respective male lines and identify other connections. (One of the Sheen women apparently believed she was a Shying.) These tests may suggest places to look for further documentary evidence – perhaps the California goldfields, perhaps a particular village in Guangzhou.

In the meantime, there are more Mak mysteries to solve and further dusty windows into Australia’s multicultural past to clean…

|

Another view of Mak's busy home.

[Un-named] Artist in China, View of Guangzhou (Canton), about 1800. Watercolour and gouache on paper 24 1/2 x 47 inches (62.23 x 119.38 cm). Peabody Essex Museum purchased with funds donated anonymously, 1975. E79708. Courtesy of Peabody Essex Museum.

|

Some other sites about Mak Sai Ying

‘A native of Canton’, Signals Magazine, Issue 123, pages 25-36, Australian National Maritime Museum.

Pigott-Gorrie Blogspot

What you can do

If you have any Chinese ancestry with a male line surname of Mak (麥) write down what you know of family stories and take pictures of any relevant heirlooms. Tell your family about them. This is worth doing whatever your ancestral surnames are.

Take part in a genetic DNA program. There’s only one prominent company, Family Tree DNA, which does a test for the male line (Y-DNA) – as well as the more common ‘cousin finder’. They have a project dedicated to Chinese family history.

You may wish to help fund DNA tests. Two tests have so far been conducted and results published in later posts. Let me know if you’d like details.

There’s still more work to do before we can find where he ended up, but we can track many of his numerous Australian descendants. Two of the several collaborative efforts are

FamilySearch and

FindAGrave. Any additions, comments or corrections you might have would be great.